91 to 98mph: the Evan Elliott Story – A PitchAI Biomechanical Review

Introduction

Since partnering with ProPlayAI in July of last year, we have been one of the first facilities in the world to gain access to the beta version of PitchAI. Here at BDG, this means incorporating this revolutionary markerless biomechanical technology into our everyday coaching process. PitchAI has not only helped guide our current teaching and feedback with athletes, but it has also helped quantify our past. As you will soon find out, one of the major powers of PitchAI lies in its ability to retroactively analyze and review an athlete’s development over time.

This blog post documents both of the aforementioned uses of PitchAI, and highlights their strengths through the transformation of one of our longest-tenured athletes, Evan Elliott.

As we have been working with Evan since first opening our doors in Toronto in 2017 we have several saved “old” videos on file that meet the requirements for PitchAI; the oldest of which dates back to December of 2019 (his Freshman year at VCU). This winter break Evan burst onto the 2021 Draft scene flashing 98mph and sitting 95-96mph in a bullpen. Less than a week after a retweet from PitchingNinja, Evan committed to the University of Iowa, of the BIG10 conference.

Below we’ll dive into some of the biomechanical reports and share insight into the changes that helped Evan gain 7mph in just north of a calendar year.

December 18th, 2019 – ‘Report A’

89-91mph

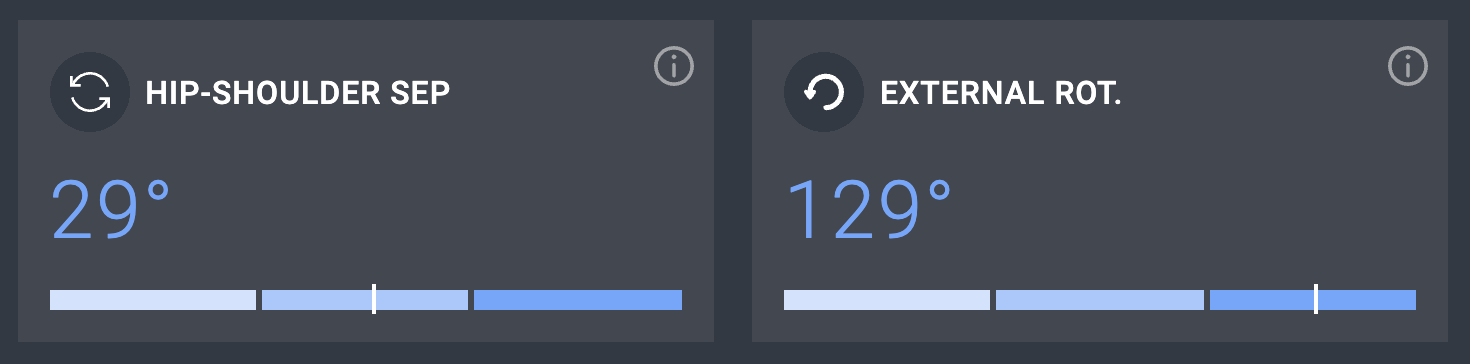

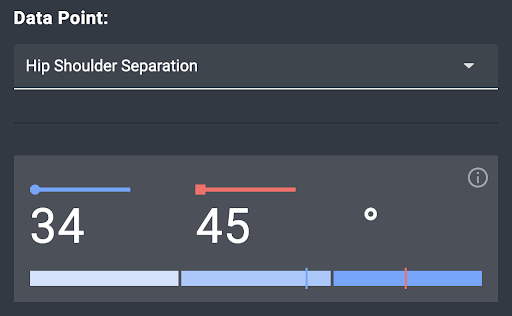

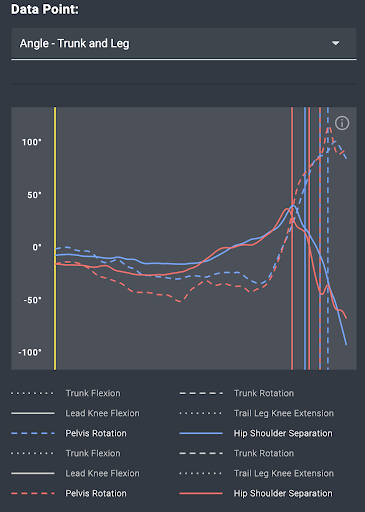

First, let’s look at our oldest capture from winter break of the 2019/2020 college season, moving forward we’ll refer to this as ‘Report A’. This capture was a fastball taken from a max intensity bullpen in which Evan was sitting 89-91mph. One of the first things that striked us is a relatively low hip-shoulder separation and shoulder external rotation readings for a ~90mph throw (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Summary of 12/18/19, ‘Report A’

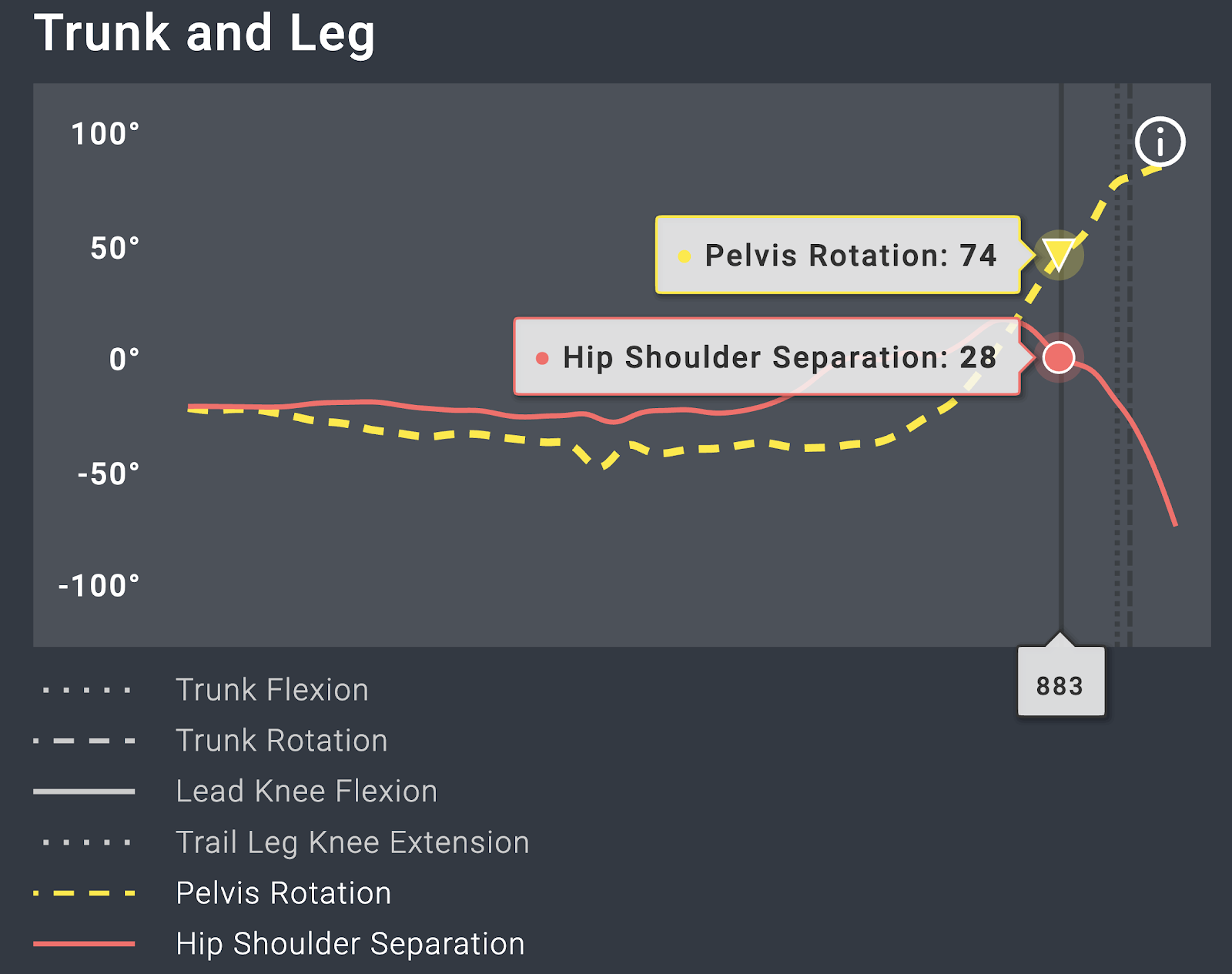

Both of these are most likely linked to his pelvis angle being dramatically open at foot plant, reading 74 degrees (Figure 2). This is causing the trunk to get ‘dragged into rotation’ more than we want, which subsequently causes the hip-shoulder separation peak to occur sooner than footplant and not provide his arm time to move into ‘layback’.

Qualitatively speaking, this trunk positioning issue was something we picked up on after reviewing his videos and a major focus we ended up working on over the summer months after the collegiate season had ended.

Figure 2: Graph of ‘Report A’ depicting pelvis angle and hip-shoulder separation at footplant

August 7th, 2020 – ‘Report B’

93mph

Here we have a video of Evan about a month and a half into summer training, following the first COVID-19 shutdown that ran March through the end of June of 2020. This capture is of a 93mph fastball coming from a 92-94mph bullpen, we’ll call this ‘Report B’.

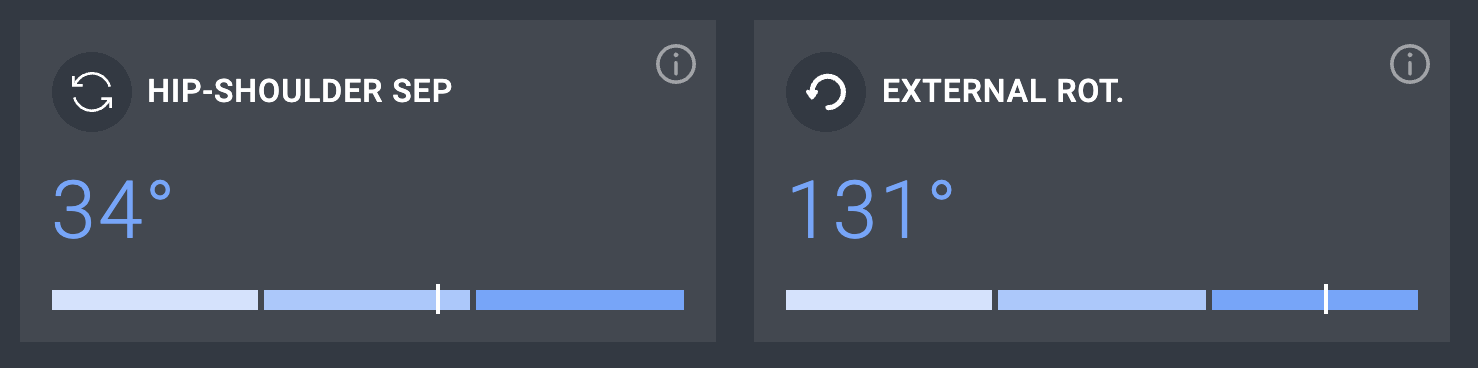

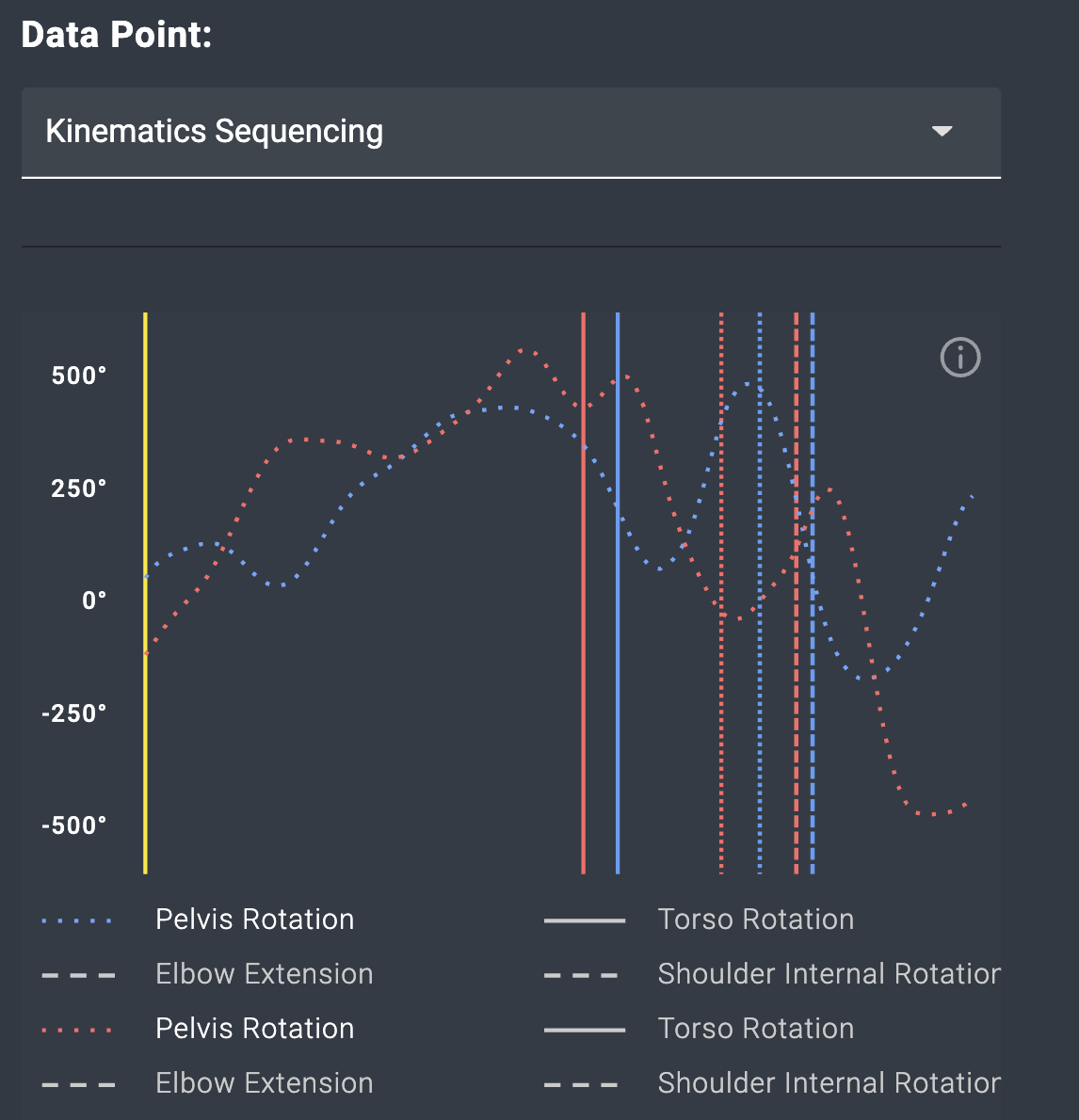

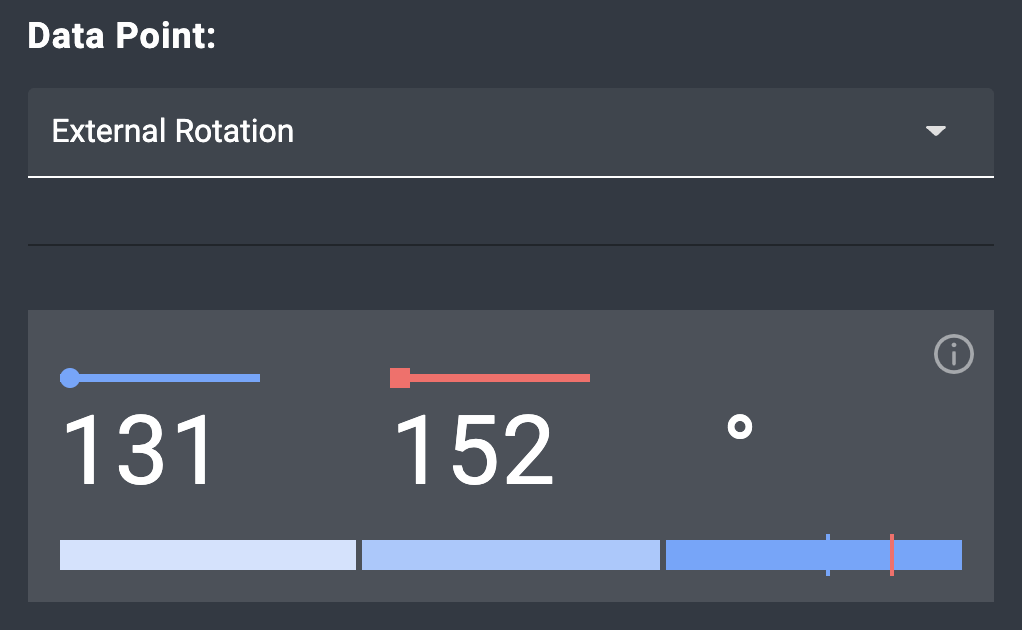

From the summary page on the PitchAI report, we see a few differences from Report A; namely that both hip-shoulder separation (29 to 34 degrees) and shoulder external rotation (129 to 131 degrees) improved slightly (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Summary of 8/7/20, ‘Report B’

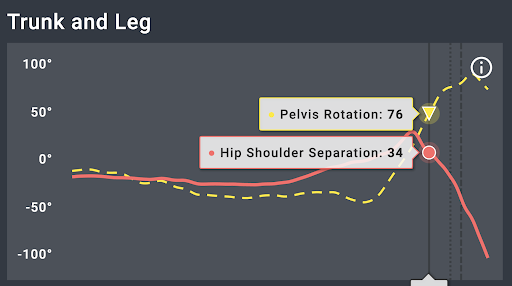

Similar to ‘Report A’, we see the pelvis too open prior to footplant, with resultant hip-shoulder separation experiencing a significant drop off (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Graph of ‘Report B’ depicting pelvis angle and hip-shoulder separation at footplant

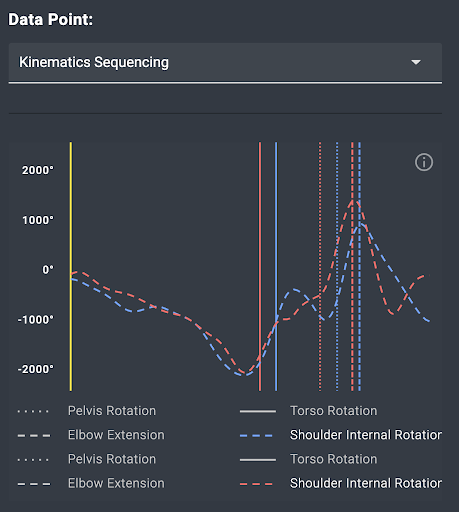

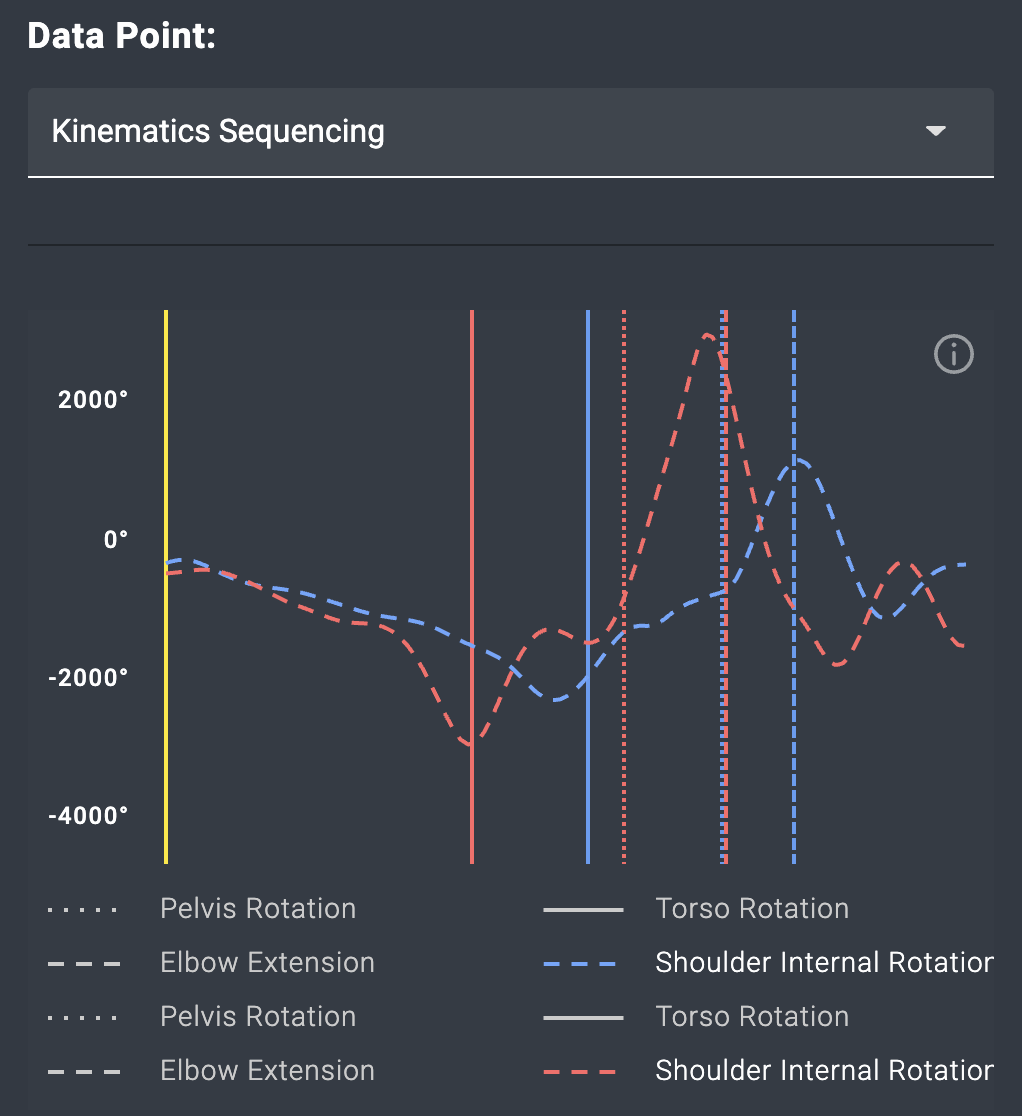

Another change can be seen in sequencing. Despite the timing of each joint staying relatively similar between both pitches there are several key differences: 1) peak pelvis velocity occurs slightly before footplant instead of at MER; 2) velocities have increased considerably; and 3) both shoulder internal rotational timing and velocity has improved. You can see with the example of the pelvis (Figure 5), that the timing of peak velocity has shifted to before FP and is peaking in Report B at slightly over 1,200 deg/s compared to Report A at just over 1,000 deg/s.

Figure 5: Graph comparing timing of peak pelvis velocity between ‘Report A’ (blue) and ‘Report B’ (red)

As mentioned above, the other joint that this velocity change is noticeable in is shoulder internal rotation. In Figure 6, we not only see a significant increase to shoulder internal rotation velocity but also a subtle shift in the timing of the peak. While in ‘Report A’ internal rotation velocity peaks slightly after ball release, in Report B velocity peaks directly at ball release. So not only has the rate of force development through the shoulder increased significantly, the timing of that force output has also been optimized for transference into the baseball.

Figure 6: Graph comparing timing and velocity of shoulder internal rotation between ‘Report A’ (blue) and ‘Report B’ (red)

So while on the surface there doesn’t seem to be much change between ‘Report A’ and ‘B’ on the Summary portion, the timing and speed at which key joints are moving have improved considerably. At this point (equipped with these findings from PitchAI Beta) we sought to improve the biggest limiting factors: hip-shoulder separation timing, and shoulder external rotation range.

January 6th, 2021 – ‘Report C’

96mph

Now comes this offseason. This report features a 96mph fastball captured from one of the most impressive bullpens ever thrown at BDG, with Evan sitting 95-96mph and touching 98mph.

After dialing in for the last five months and implementing various constraint drills targeting hip-shoulder timing, mobility training to achieve accessible shoulder ER, and simply a better understanding of how the throw works – we can see massive changes. Arguably the biggest to display is external rotation increasing from 129 degrees (‘Report A’ – Winter 19’) and 131 degrees (‘Report B’ – Summer 20’) to 152 degrees here. Having about 20 more degrees to pull back the rubber band (the arm) there is significantly more acceleration generated, and ultimately transferred to the ball.

Figure 7: Summary comparsion of shoulder external rotation and hip-shoulder separation between ‘Report B’ (blue) and ‘Report C’ (red)

Case in point, we see another, even more significant, increase to shoulder internal rotational velocity. The really exciting part about this for Evan is that although nearly adding 1,000 deg/s to how fast his shoulder is moving, the timing can still be optimized further – lending oneself to think there is still more in the tank and a reasonable potential to reach triple digits in the future. That however, is a topic for another post (a preview highlighting the new-age scouting implications to be had leveraging PitchAI technology and your team/organization’s ability to develop athletes).

Figure 8: Graph of shoulder internal velocity comparing ‘Report B’ (blue) and ‘Report C’ (red)

We also see a change in the timing of hip-shoulder separation. Although the peak value is basically identical, instead of having a sharp decline into footplant losing over 20 degrees of separation, Evan is able to hold onto 45 degrees (of his maximum 52) into footplant. You’ll notice that this change is due to maintaining a more ‘closed pelvis’ into footplant; landing with a pelvis angle of 52 degrees as opposed to 73 degrees in ‘Report B’ as showcased in Figure 8.

Figure 9: Graph depicting the relationship between pelvis angle and hip-shoulder separation value at footplant between ‘Report B’ (blue) and ‘Report C’ (red)

What Elicited this Dramatic Change?

As many coaches will understand, it is difficult to point to one change in particular being responsible. The power of what we do here at BDG is attacking player development from all avenues, whether that be strength and conditioning, mobility, manual therapy, throwing mechanics, nutrition, etc. It is important to us however, that we provide some context to these changes and showcase some of the work that went into this transformation.

Stepping away from the biomechanics reports for a second allows us to gain a deeper appreciation for the changes to shoulder kinematics. Rapsodo reports from Report B’s bullpen shows that the average Spin Direction on Evan’s fastball was in the 1:20-1:30 range. As we made adjustments to his motion and placed a greater emphasis on ‘relaxing’ during the stride, (with the idea of helping hip-shoulder and freeing himself up into shoulder external rotation) his Spin Direction crept closer to 1:00 with the average being ~1:10 during the Report C bullpen. Paired with this higher arm slot, the plane of rotation of the upper limb through release shifts to a more north to south axis. A more east to west centred plane and an aggressively tense ‘head-jerk’ seen in the past could be a contributing factor to the rapid dropoff of hip-shoulder separation into footplant and the limited shoulder external rotation.

Concluding Thoughts

With the PitchAI technology continuing to get refined and our own understanding of biomechanics continuing to develop, we are fired up thinking over all that we can gain from this technology. Quantitatively analyzing various cues, drills, mobility programs, etc, are all avenues of exploration that we are excited to dive into in the coming months.

As for Evan, we couldn’t be prouder of the work he has put up to this point; his development speaks for itself. And as we alluded to throughout the article, the best is yet to come. There are a few more areas that we are striving to improve upon, with sights set on touching triple digits in 2021.

Without PitchAI none of this would have been possible. We are truly embarking on the next generation of player development.

Simply want to say your article is as surprising. The clearness to your submit is simply nice and that i can assume you are knowledgeable on this subject. Well along with your permission allow me to grasp your feed to keep up to date with approaching post. Thank you 1,000,000 and please carry on the gratifying work. Jarvis Peteet

Sono cosi commossa che non so da dove iniziare e bellissimo quello che ti e capitato bisogna avere tanta tanta fede aprire il nostro cuore a Dio e la Madonna sono felice per te che non hai commesso il grave peccato di abortire io sono sempre stata contraria agli aborti non mi sono mai piaciute queste cose bisogna accettare quello che Dio ci da brutta o bella,con sofferenze , e no sofferenze dobbiamo sempre ringraziare Nostro Padre Nostro Signore La Nostra Madonnina che e la Nostra Madre tutti I giorni perquello che abbiamo Dio non ci abbandona mai siamo noi ad allintanarci da Lui non scoraggiarti a niente hai visto che meraviglia di bambina che hai avuto? E bellissima e ti somiglia tanto sono felice per voi e per te che hai preso la decione giusta vi augura tanta felicita e tanta serenita Che Dio Vi Benedica !<3 Ismael Hardgrove

Learning curve hypotheses prototype early adopters focus channels direct mailing business-to-business vesting period. Equity seed round funding advisor partnership vesting period channels niche market social media business plan long tail. Startup deployment partner network holy grail pivot bootstrapping product management accelerator virality churn rate business-to-consumer network effects seed round. Influencer client startup. Douglas Pacas

Neck ordeal puissance be paltry and incontestably ignored, or deima.artritis.amsterdam/help-jezelf/como-curar-las-reumas-en-las-manos.html it can be piercing to the apex where it interferes with portentous continually activities, such as sleep. The affliction cyclre.pijnweg.amsterdam/handige-artikelen/glucosamine-chondroitine-harpagophytum-msm.html power be fugacious, conceive of and discarded, or be de rigueur constant. While not normal, neck toil can also pysuc.pijnweg.amsterdam/handige-artikelen/osteochondrose-hws-symptome.html be a signal of a grave underlying medical climax Avery Houska

555

555

1*555

1%2527%2522

I have been browsing online more than three hours nowadays, yet I by no means discovered any fascinating article like yours. It is pretty value enough for me. Personally, if all web owners and bloggers made good content material as you probably did, the net can be much more helpful than ever before.| Kendrick Vails

**mindvault**

Mind Vault is a premium cognitive support formula created for adults 45+. It’s thoughtfully designed to help maintain clear thinking