91mph to 98mph: The Evan Elliott Story – A Movement Review

Introduction

Lennon just took you through the biomechanical review of the changes we saw over the past few months using PitchAI with our guy Evan Elliot, which I will link here. This post serves to act as a complementary piece to his article, and shed further light on the holistic process that led to Evan’s staggering velocity development. I will be referencing his article and the PitchAI reports he references constantly throughout this post, and will henceforth refer to his comments in “red”.

“As many coaches will understand, it is difficult to point to one change in particular being responsible [for change]. The power of what we do here at BDG is attacking player development from all avenues, whether that be strength and conditioning, mobility, manual therapy, throwing mechanics, nutrition, etc. It is important to us, however, that we provide some context to these changes and showcase some of the work that went into this transformation.”

And that is just what we are going to do. In particular, we will be discussing the strength, mobility, and therapeutic interventions that helped push Evan beyond his previous limits. Some brief background: I have been working with Evan since he came to BDG several years ago as one of his S&C coaches, and as his therapist since August of 2020. Though I have been able to keep a rough record of the S&C programming he has had since beginning training with us, this summer was the first time I was able to get hands-on and assess his joint capabilities on the table.

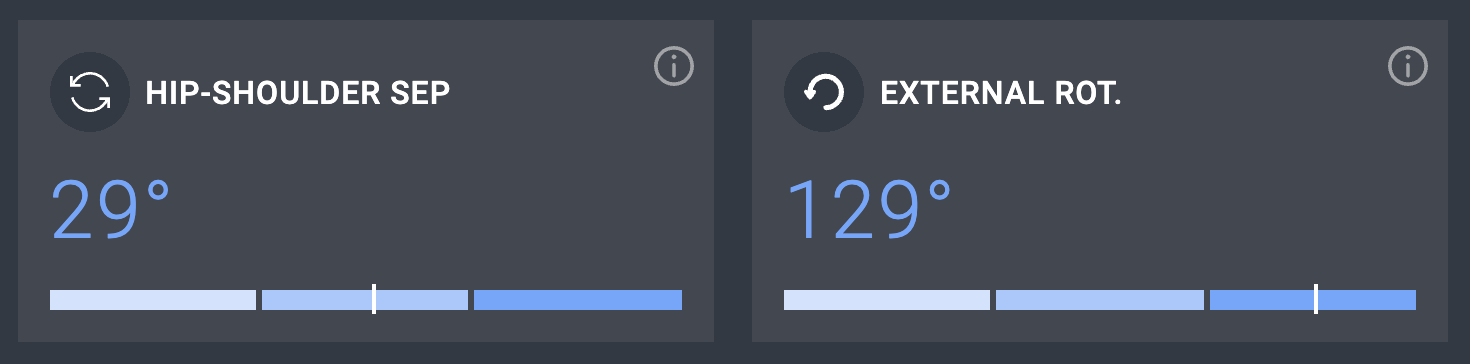

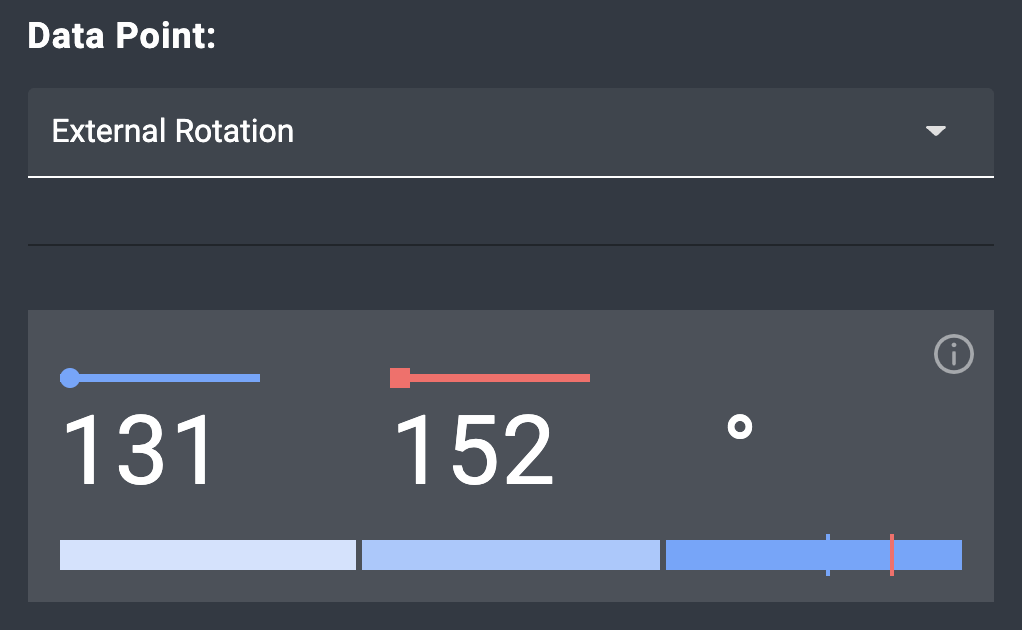

Although our first PitchAI report dates back to December of 2019 (Report A in Lennon’s review), my comments will focus on reports ‘B’ and ‘C’. Seeing as how he was already approximately one month into training during Report B, I do want to include the Hip-Shoulder and Shoulder external rotation joint angle measurements (Fig. 1) from Report A, just to provide some form of baseline.

Figure 1: From ‘Report A’ (89mph) in December, 2019 the earliest PitchAI report generated

Before going further I do want to state that all of this is predicated on Evan’s relentless work ethic and determination. All the help in the world won’t do anything if you don’t put the time in yourself as an athlete and grind.

Evan is one of those guys.

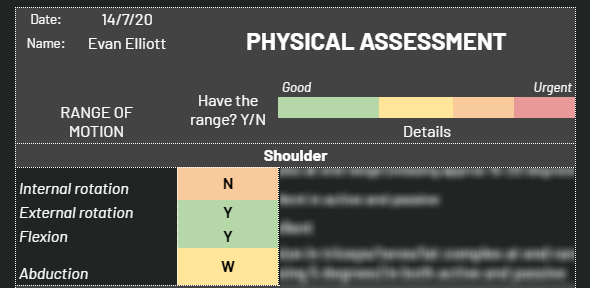

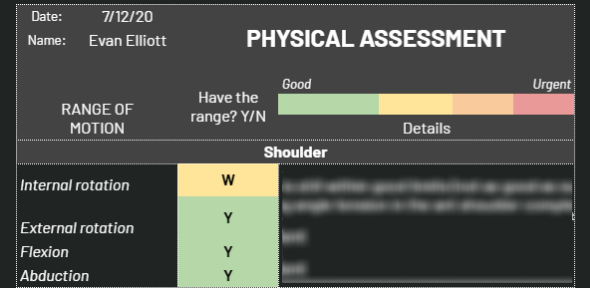

Now, the next thing I want to touch on was Evan’s on-table assessment findings from July 14, 2020 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Approximately one month prior to ‘Report B’; demonstrates a condensed version of our joint assessment (Note that colour coding is for internal consistency and is not indicative of pathology)

As you can see, when Evan reported to BDG post lockdown, there were a few issues that I saw with him on the table. The biggest mobility problems were in shoulder internal rotation, and spinal rotation about the thoracolumbar (TL) junction. From what we know about throwing shoulder total arc ROM, we want approximately 180 degrees of external plus internal range. While passive external range was good for Evan, there was some end-range posterior capsular stiffness coming out of the lockdown. Regarding his spinal rotation, there was some stiffness and mild cramping in the lats (the greatest contributor to unilateral spinal rotation) and some neuromuscular control deficiencies in the mid spine.

We came up with a treatment plan that involved soft-tissue work, spinal rotational mobilizations, shoulder external rotation PAILs/RAILs, spinal extension and rotation PAILs/RAILs, and latsPAILs/RAILs amongst a host of others to target joint ROM and end-range strength. To see examples of how these are performed, click to see a complete list here.

His lifting program focused primarily on returning to heavy resistance. Being at home meant he hadn’t been able to lift consistently for the couple of months prior, save for some occasional access to a home gym. Following our in-house strength assessment, a standard general strength accumulation program was implemented for the summer training period. Within this program, our primary strength goals were in pulling and hinging pattern development.

“Below we’ll dive into [two] biomechanical reports and share insight into the changes that helped Evan gain 7mph…”

August 7th, 2021 – ‘Report B’

93mph

“This capture is of a 93mph fastball coming from a 92-94mph bullpen.”

Figure 3: Summary of 8/7/20, ‘Report B’

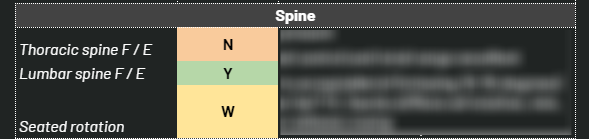

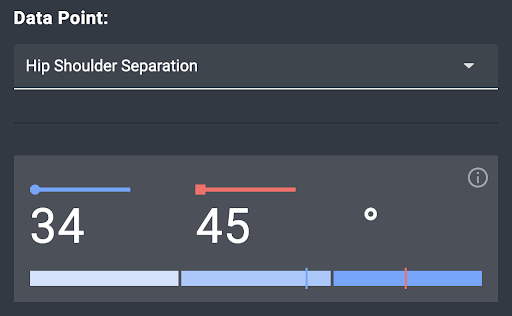

There are some subtle changes when compared to Report A; “namely that both Hip-Shoulder separation (29 to 34 degrees) and shoulder external rotation (129 to 131 degrees) improved slightly (Fig. 3)”. Because the first PitchAI analysis in Report A is from December of 2019, we can’t say for certain that these changes are due to the interventions we incorporated in his training and the treatment provided since his July assessment – but it clearly played a contributing role.

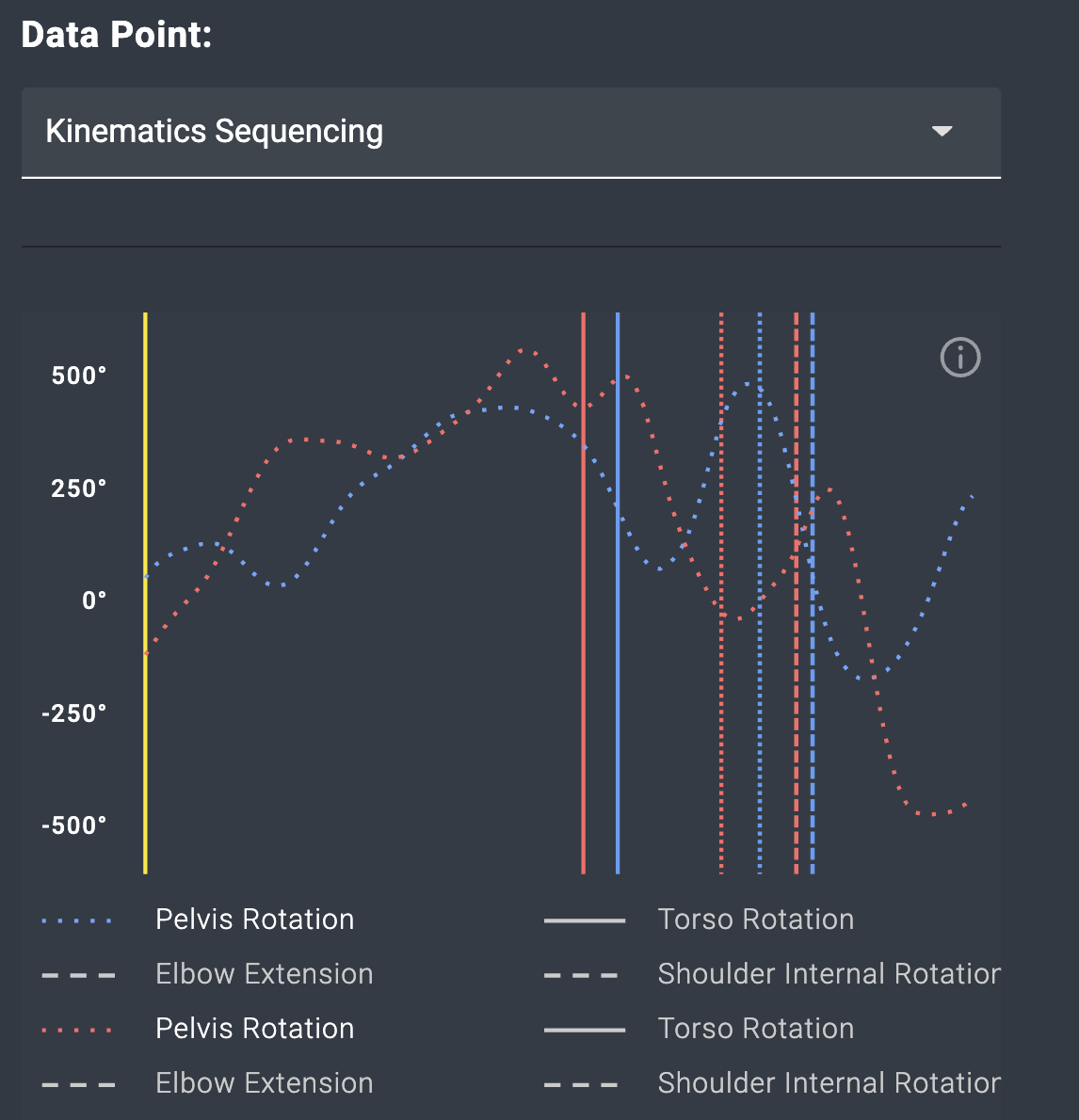

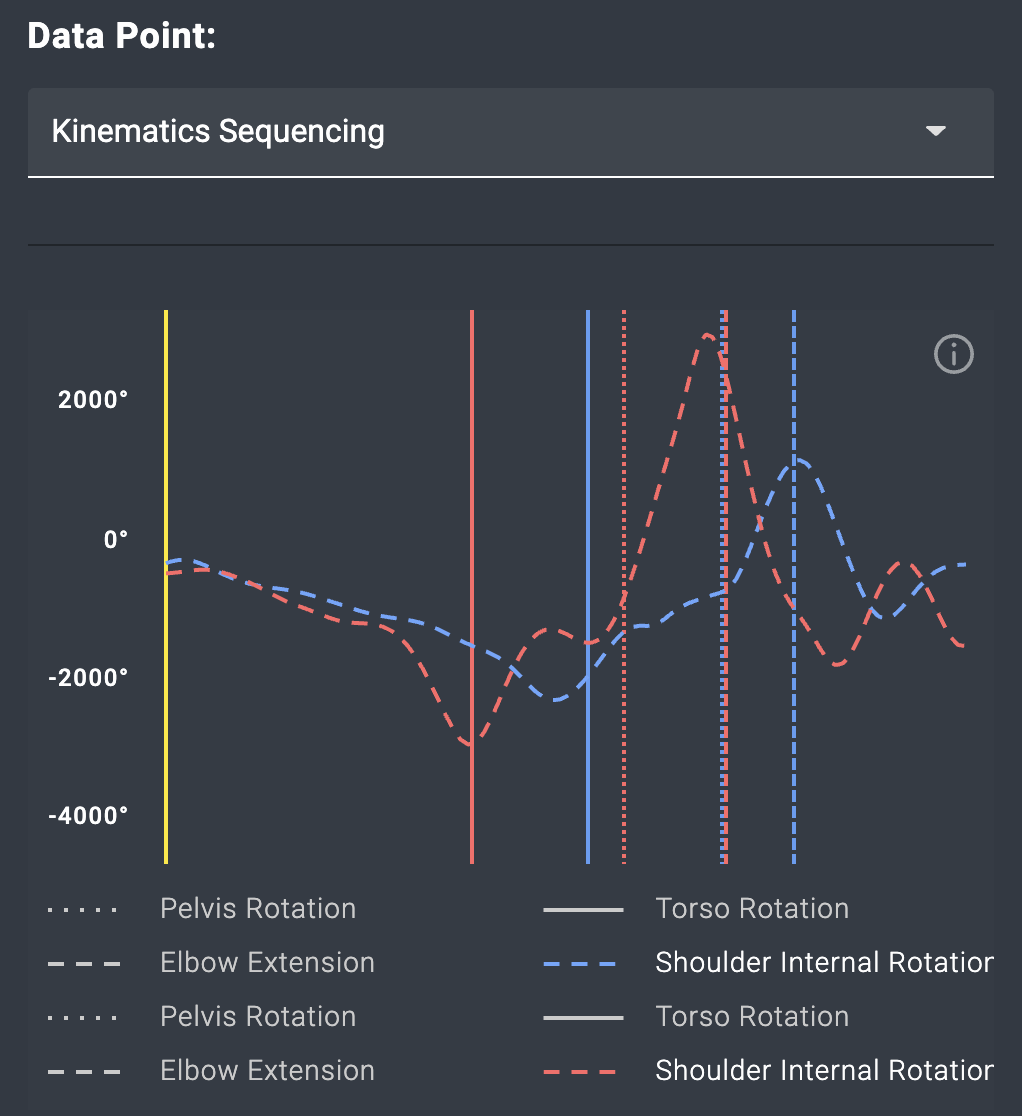

Having established we have a ROM improvement from Report A to Report B, I also want to comment on the changes that were made in peak joint velocities.

“Despite the timing of each joint staying relatively similar between both pitches there are several key differences: 1) in general all (including pelvic) velocities have increased considerably; and 2) both shoulder internal rotational timing and velocity has improved.”

If we look at the pelvis (Fig. 4a), we can see that it is peaking in Report B at slightly over 1,200 deg/s compared to Report A at just over 1,000 deg/s. We can see similar improvements in shoulder internal rotation velocity (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4a: Graph comparing timing of peak pelvis velocity between ‘Report A’ (blue) and ‘Report B’ (red)

Certainly some of the credit goes to throwing constraints and drill work that Lennon implemented with Evan (more responsible for the shift in peak velocity timing/ sequencing in my opinion), but I believe that the increase in rotational velocities is due to him being back in the weight room, re-establishing his strength and power from consistent 4-5x/ week training.

Figure 4b: Graph comparing timing and velocity of shoulder internal rotation between ‘Report A’ (blue) and ‘Report B’ (red)

Evan would continue to train with us for another few weeks after Report B was analyzed, and then he took off for the fall to train at school. He would go on to dominate the fall season, posting a 1.23 ERA with 32 K’s in 15 innings while at Prairie Baseball Academy in Alberta. We kept in touch with Evan via online training, and monitored his ROM and mobility with a program tailored to his throwing schedule.

Then he came back for winter break.

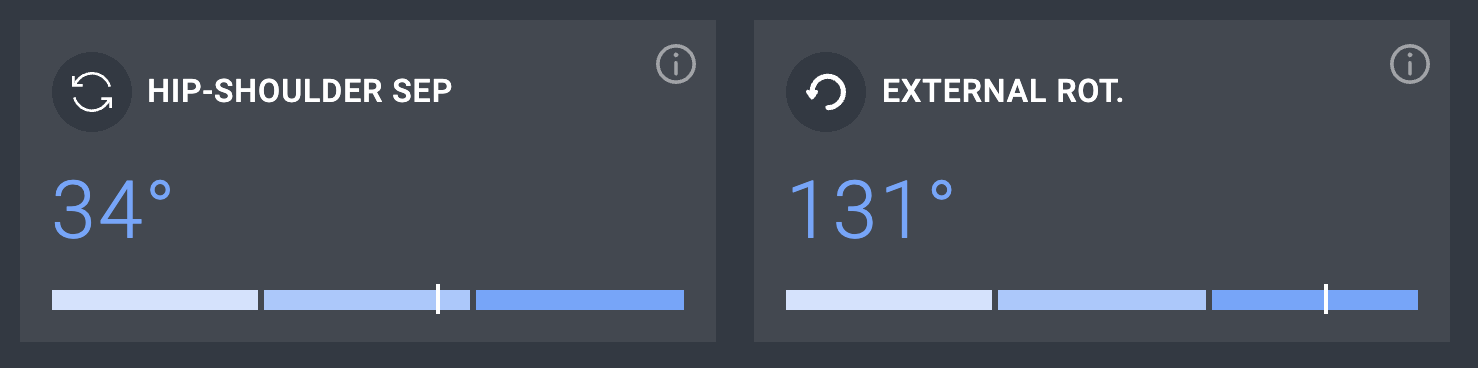

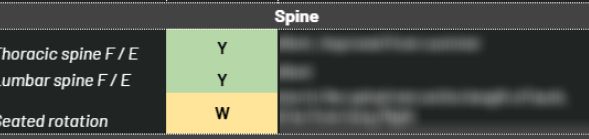

On his first day back we got the big guy back on the table to check out his active and passive joint ROM, the highlights of which can be seen below (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Approximately one month prior to ‘Report C’, right after coming back to BDG from his fall season, demonstrates a condensed version of our joint assessment (Note that colour coding is for internal consistency and is not indicative of pathology)

As you can see, there have been significant improvements made since his last assessment. His shoulder internal rotation range cleared up, and there were significant improvements in spinal capabilities. His overall excursion improved, as did his segmental control about the TL junction (mid-spine) – both adaptations a result of consistent, focused training. For change to be more than temporary, it needs to be repeated consistently over time, again and again. We had trained the hell out of his end-ranges in external rotation and spinal rotation, improving neuromuscular control and strength.

This time our strength assessment revealed Evan needed to improve his absolute pressing strength, and his hamstring strength and power. In part due to a conversation with Evan, we found he wasn’t getting very much hamstring recruitment during hinge pattern exercises like the ‘TBDL’ or ‘RDL’. We were able to throw him into a ‘Nordic’ that immediately lit his hamstrings up, causing them to cramp – a major sign of weakness in a muscle group.

We moved away from our standard training and made the switch to cluster-based training for all his primary and secondary lifts. They’ve been something we have been using with our high-end athletes that have a multi-year history in strength and power training and so far have been yielding great results. As an example, after two weeks of targeted hamstring strength his supine hip thrusts exploded from 235 to over 400lbs.

Fast forward a month of training, and we finally arrive at Report C.

January 6th, 2021 – ‘Report C’

96mph

“This capture features a 96mph fastball captured from one of the most impressive bullpens ever thrown at BDG, with Evan sitting 95-96mph and touching 98mph.”

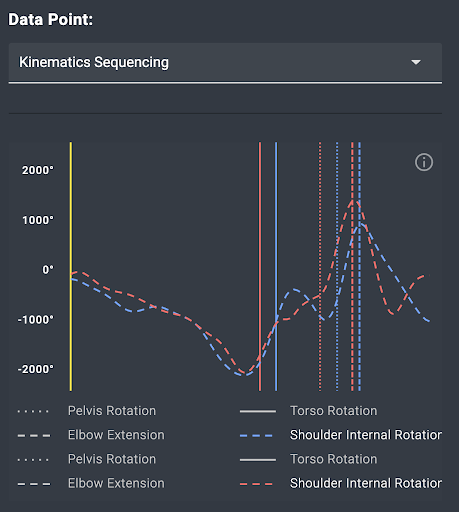

Again, we see shoulder external rotation increasing from 129 degrees (Report A, Winter 19’) and 131 degrees (Report B, Summer 20’) to 152 degrees here (Fig. 6a).

Figure 6a: Summary comparison of shoulder external rotation between ‘Report B’ (blue) and ‘Report C’ (red)

In Report C, we see another massive increase to shoulder internal rotation velocity (Fig. 6b). While this is partly due to his increase in available shoulder external rotation, I am confident in saying that it is also a direct result of the improvement in pressing strength and hamstring power. Yes, the hamstrings are far away from the shoulder, but the more force we can generate earlier on in the delivery means there is more force that can be transferred to the upper body.

Figure 6b: Graph of shoulder internal velocity comparing ‘Report B’ (blue) and ‘Report C’ (red)

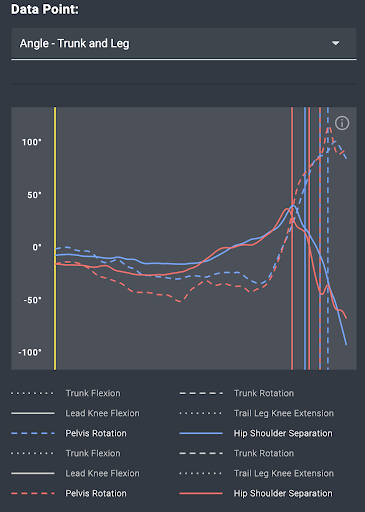

When we look at Hip-Shoulder separation we see that Evan is able to hold onto 45 (of his maximum 52 degrees) into footplant (Fig. 6c).

“You’ll notice that this change is due to maintaining a more ‘closed pelvis’ into footplant; landing with a pelvis angle of 52 degrees as opposed to 73 degrees in Report B.”

We already saw the improvements in the tissue range and quality in his spine, and I think that these changes were largely responsible for the dramatic shift in Hip-Shoulder. Rather than his system having poor neuromuscular control and strength at that separated position at footplant, he was able to hold on to it longer, allowing for far better energy transfer up the kinetic chain. These changes were spurred by his continuous use of our end-range spinal rotational exercises, and some position mastery that included some diaphragmatic work.

Figure 6c: Summary comparison of hip-shoulder separation between ‘Report B’ (blue) and ‘Report C’ (red)

Figure 6d: Graph depicting the relationship between pelvis angle and hip-shoulder separation value at footplant between ‘Report B’ (blue) and ‘Report C’ (red)

Another point I think worth making is that his improvement in thoracic extension likely has a hand in the improvement in layback we saw. The shoulder is composed of both the glenohumeral joint and the scapulothoracic joint (a pseudo joint, but important nonetheless). An improvement in thoracic mobility would likely enable better scapular motion, and promote further improvements in shoulder external rotation.

Final Thoughts

There is still a lot of work to be done, and we need to continue to replicate this process with more of our athletes. The beauty of this is the ease of access that PitchAI provides us – it’s now far easier to relate on-table findings to biomechanical findings. We no longer have to undress athletes, attach 40+ markers, or own multi-thousand dollar biomechanics labs. From a long-term adaptation perspective, it allows every therapist, strength coach, and pitching coach the ability to objectively monitor the progress trying to be made.

From a pre-post treatment perspective, this is game changing. Being able to immediately compare on-table findings and therapeutic interventions with biomechanics data is really important. The ability to confirm or refute that our chosen intervention is an appropriate one within the span of a few minutes is an absolute game-changer. While this is not something we directly tested with Evan, it is something we are doing with a few of our current rehab cases, and we are finding some really interesting things. **Hint – your treatment specificity from a ROM perspective is not that important (though a physiological perspective might disagree with that).

From a holistic perspective, being able to share this information between practitioners, or members of a performance team is important. PitchAI helps keep people on the same page, and removes a lot of the human error and personal bias that is present during our assessments and re-evaluations. It’s a lot harder to argue that a pitcher needs ‘x’ or ‘y’ when PitchAI clearly shows that in fact they need better ‘z’. It helps the therapist and pitching coach talk about where there is discomfort or lack of good joint motion. It helps the therapist and strength coach determine an effective exercise protocol for rehab and performance development. And it helps the pitching coach and strength coach collaborate on designing effective drills and training. Lennon and I have been able to communicate with each other at a much better clip, as cross-talk has been made easy – we can all agree on data. As you saw above, if Hip-Shoulder needs improvement, then attacking that from multiple sides at the same time is going to prove beneficial. Access to information is always a good thing, and the upside this technology has for facility wide collaboration is huge.

Excited to keep moving forward.

**mindvault**

Mind Vault is a premium cognitive support formula created for adults 45+. It’s thoughtfully designed to help maintain clear thinking