Baseball Research Review #5 – Injuries and Attentional Focus

In this week’s edition of the Baseball Research Review we take a look at a recent study by Dr. Rob Gray on post-injury attentional focus. This is — as far as we are aware — the first study to look at where athletes focus their attention following an injury: Is their attention directed inwardly (e.g., to the position or motion of a limb or other body part) or outward (e.g., towards whatever movement goal they are trying to execute). For more information on attentional focus, we encourage you to check out our ongoing article series, “Performance Under Pressure”.

Authors: Gray, Rob

Background:

In the performance world, there has been considerable thought and investigation into the subject of attention and it’s relation to optimal performance outcomes. The sport expertise literature is chock full of research examining where athletes direct their attention during goal-directed movement, and has helped develop this idea of “internal” versus “external: focus of attention. Similarly, the motor learning literature has sought to identify the effects of attentional focus on the acquisition, retention and transfer of motor skills.

An internal focus of attention involves focusing on the execution of one’s own body movements — like thinking about what your elbow is doing at front foot contact during a pitch, or what your hands are doing while you load the barrel of your bat during a swing.

An external focus of attention involves focusing on the outcomes of one’s movements — like hitting the catcher’s mitt, or driving the ball in the air.

Whether it is advantageous for athletes to focus their attention internally or externally likely depends on context. The literature has mostly supported an external focus over an internal focus with respect to both performance and learning outcomes. However, we would like to suggest (respectfully) that — while an external focus of attention is probably desirable in most sporting contexts — the answer to “where should athletes focus their attention?” may not be as black-and-white as many make it out to be.

For instance, when an athlete is required to alter or fine tune his or her technique in a particular motor skill, shifting an athlete’s attention internally may be an effective way to destabilize a deeply-ingrained motor pattern. (Carlson & Collins 2011, Gray, 2015).

That being said, the situations in training or competition where an internal focus of attention is beneficial are likely limited. And, we think it is reasonable to suggest that, most of the time, we want to encourage our athletes to focus on the task they are trying to accomplish, rather than on the specifics of how they are going to get the job done.

It has been suggested that when an athlete suffers an injury they are prone to adopting an internally-directed focus of attention (Arden et al 2013). With the abundance of internal cues in many rehabilitation settings, it is hypothesized that this internally-directed focus of attention may stick after the athlete been cleared to play, and could potentially create a disruption in long term performance.

This study addresses the following questions:

- Do post-injury athletes maintain an internally directed focus?

- And, does it impact performance?

The study includes two separation experiments: one investigating hitters and the other pitchers. The purpose and design of each are very similar, so we will only address the discrepancies between the two, rather than outline them both in full.

Purpose:

The purpose of each experiment was to evaluate the differences in attentional focus between expert players recovering from injury and two control groups: non-injured experts & novices. Experiment 1 was directed at baseball batters. Experiment 2 was directed at baseball pitchers.

Methods:

In each experiment, three different groups were used and included 10 experts who were previously injured, 10 non-injured experts, and 10 participants who had never played baseball at all. The criterion for post-injury hitters were ACL tears (UCL in pitchers) treated surgically within the last 18 months, who had played competitive level baseball for at least 10 years prior to injury and were medically cleared to compete.

The procedure was performed as follows:

- In each experiment, a simulator was used to perform a primary task. Pitchers were asked to throw a baseball into a strike zone and hitters to swing at an incoming simulated pitch. The specific logistics and specifications of the setup are intricate, but have been successfully used in a number of previous studies by Gray.

- Batters and pitchers were asked to perform ‘secondary tasks’ while hitting or pitching.

- During the initial 8s of each trial, a probe was randomly displayed on the screen, and used for the secondary ‘ball task’.

- At a random time after the ball was projected on the screen, an auditory tone was presented with one of four prompts; “none, leg, arm or ball”.

- At the end of the task, the participants were required to answer a question related to their prompt – a means of identifying how attentive they were to that area.

- For example: in the “leg” prompt for hitters, they assessed whether their lead leg was closer to being fully bent or straight at the instant the auditory tone was presented. The hitters would answer with either ‘bent’ or ‘straight’, which was then compared to live kinematic data.

*The hypothesis being that if a player displayed an internal focus they would be significantly better at correctly answering the secondary tasks.

- Batters completed 100 trials separated into 4 blocks to reduce the accumulation of fatigue.

Results:

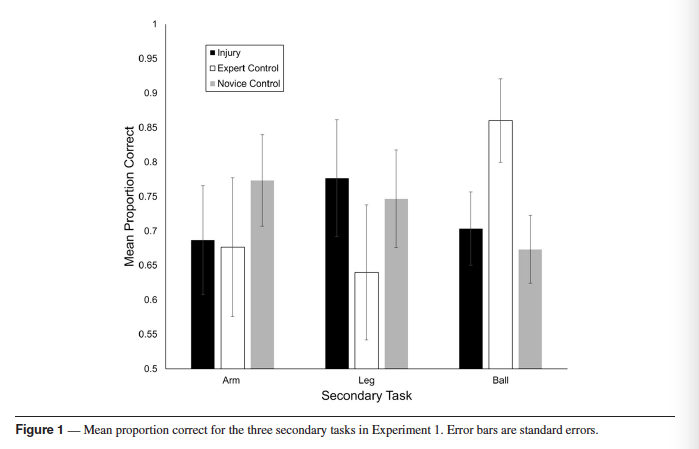

Experiment 1 — Batters

The results of Experiment 1 were consistent with the authors predictions.

“Relative to the expert control group, the mean proportion correct was significantly higher for the injury group in the leg condition [t(18) = 3.34, p = 0.004] and significantly lower for the injury group in the ball condition [t(18) = -6.15, p <0.001].”

The mean proportion of hits for the injury, expert and novice control groups were 0.42 (SE = 0.7), 0.69 (SE = 0.8) and 0.29 (SE = 0.7).

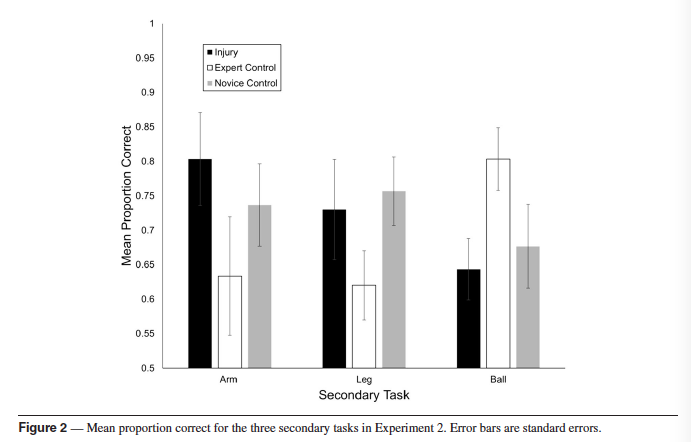

Experiment 2 — Pitchers

“Relative to the expert control group, the mean proportion correct was significantly

higher for the injury group in the Leg condition [t(18) = 4.92, p < .001] and the Arm condition [t(18) = 3.93, p < .0001], and significantly lower for the injury group in the ball condition [t(18) = –5.92, p < .0001].”

The mean proportion of strikes for the Injury, Expert Control and Novice Control groups were 0.69 (SE = .09), 0.83 (SE = .04), and 0.54 (SE = 0.8).

Discussion:

One of the biggest issues we see with coaches & players reading the research is that they take statements like the one above from an abstract or conclusions section and walk away. We actually chose this article in part to highlight the issues with ‘abstract reading’ or ‘conclusion scouring’.

Let’s look at what the author of the study concluded,

“It is proposed that the key take-home messages relevant to practice are (i) as it is commonly believed, athletes recovering from injury appear to have an internal focus of attention when executing their skill, (ii) this internal focus is associated with inferior performance relative to comparable non-injured athletes, and (iii) a return to a high level of performance will require the readoption of an external focus of attention in the long run.”

Without actually undressing the study, its limitations or the litany of research surrounding it, one can easily misinterpret Gray’s conclusion.

What we don’t want people to conclude from this study is “boom, more evidence for external cueing. Anyone who creates internal focus is an idiot.”

We live in a world that is seldom black and white.

The author does a tremendous job describing the implications of these findings and the limitations to the study. The depth of his discussion is a great example of why it’s necessary to decompose AND digest the entire study — and not just reiterate the findings.

Attention and Injury

The results show clear evidence to support the authors primary hypothesis; that post-injury players would display an internally directed focus similar to that of a novice group on a secondary task. Moreover, in both experiments, the injured athletes were better able to make judgements about their injured area in a secondary task relative to experience matched controls.

In the hitter group, the post-injury batters were more accurate judging their previously injured knee than their arms. Thus, hitters displayed a localization of internal attention. This was not seen, however, in pitchers. The results on the secondary tasks were similar between the injured (arm) and non-injured area (leg).

The author proposes that this localization difference between hitters and pitchers comes down to biomechanics. That the interplay between the lead leg and arm mechanics are so intertwined that poor lower half mechanics may be translated up the chain.

Attention and Performance

According to the data one can certainly conclude that there is an association between internally directed focus and poorer performance. Key word – association. Having said that, and echoing what Gray talked about in his discussion, there are a number of limitations and further questions to be asked.

- Was the poor performance a result of an athlete’s lack of training leading up the experiment?

- Are the athletes in the process of re-learning or altering movement techniques? If so, then we would expect them to adopt an internal focus.

- Was it a result of a lack of automaticity in their movement?

- Was it a result of not being in a competitive scenario recently and therefore succumbing to the effects of pressure?

Moreover, and without getting into a heated discussion on the topic, is there any research to suggest that expert performance requires both internal & external focus?

Well, if you look at what Toner & Moran’s prereflective and reflective work, you might not be so quick to jump to the conclusion that external focus is always optimal. As an example, take a look at this recent study that showed basketball shooting performance decreased with an external focus relative to an internal one.

The surfacing of these thoughts and ideas are exactly why we believe that coaches & therapists should be reading research with a more critical mindset. More often than not, we encounter coaches who proclaim to read or review research only to discover that they’re ‘abstract browsers’. This study is a perfect example of how much depth, understanding and insight we can collect with appropriate lens.

It is why we go into a lot of depth on a topic. Why our reviews aren’t 4 or 5 sentences long regurgitating the abstract.

Again, we hope that you enjoyed this study and look forward to continue to provide them in the future. If you have any questions, suggestions or comments please let us know in the comments below.

Generating a discussion on these subjects is a goal of ours — we want to spark a conversation on the presented ideas and theories, not to be viewed as ‘correct’.

Major Takeaways:

- Internal focus is generally expected post injury, and was displayed in both hitters and pitchers.

- An internal focus may be beneficial in certain circumstances such as an expert learning a new technique.

- An association does not necessarily imply a causation. Readers need to be wary of jumping to the conclusions section or, even worse, reading simply the abstract.

Until next time,

Dr. Stephen Osterer

If you like what you’ve read, and you’d like to receive updates about future instalments of the Baseball Research Review, be sure to sign up for our newsletter using the form below.