Workload Management in Season: From Closer to Starter

A few days ago, I posted on our Facebook group describing two very different scenarios that a couple of our clients went through this season. Both were college pitchers with a history of elbow pain that had restricted their innings and performance in the season prior. If you’ve already read that post, this article is just a deeper look into Pitcher B’s experience. If you haven’t read that post, then I ask you to imagine the emotion that Pitcher B felt throughout the described chain of events.

On February 17th, 2016 I received the following text from one of my college guys, a Junior right-handed pitcher playing at the DIII level:

“I threw great today. Good control, good movement, good velo, way better mechanics. I feel great. The velo is getting better every week. This is the best I’ve ever felt heading into season.”

To give you a little history, this athlete (who will remain nameless) sent me an email pleading me to help him “do whatever it takes” to get healthy, and take a run at playing baseball after college. In our initial conversation he mentioned to me how the game wasn’t as fun as it used to be; he was frustrated with his lack of development, discouraged by persistent arm issues, and lost in a sea of information.

He had a long history of elbow pain, which eventually led to Tommy John surgery three years prior, and was followed by peaks and valleys in arm health since. Last year, in his sophomore season in college, he sat around 84-86 MPH, consistently pitched with pain, and, overall, hadn’t really garnered many competitive innings in college.

The idea of this kid throwing in competitive games safely was challenging in and of itself, let alone helping him reach his goal of playing professional baseball.

But as I dug deeper into this athlete’s history, I found out that not everything about his past was necessarily working against him:

- He was an extremely hard worker, having shown the determination to lose 50 lbs with no external aid.

- He had a history of misapplied training. He could deadlift 600 lbs, but rarely (if ever) trained high velocity.

- He had been exposed to relatively little skill-specific coaching, and instead had resorted to learning whatever he could off the Internet.

- My physical assessment identified a number of key joint and movement limitations that I felt could help (at least partially) explain his history of health issues and sub-par fastball velocity.

- Slow-motion video analysis corroborated the findings from my physical exam, so I felt confident that there were areas of focus we could exploit for immediate velocity gains.

Basically, we had a lot to work with.

Cautiously optimistic with my findings, I told the player that our priority was to first get him healthy and into competitive innings in time for his Junior season, and then be aggressive with velocity gains in the off-season leading up to his senior year. My goal was to break the chronic pattern of his brain’s marriage of pitching and pain, potentially re-wiring a problematic neurotag, and help him re-associate pitching with feelings of confidence, control, and, most importantly, fun.

He bought into the idea.

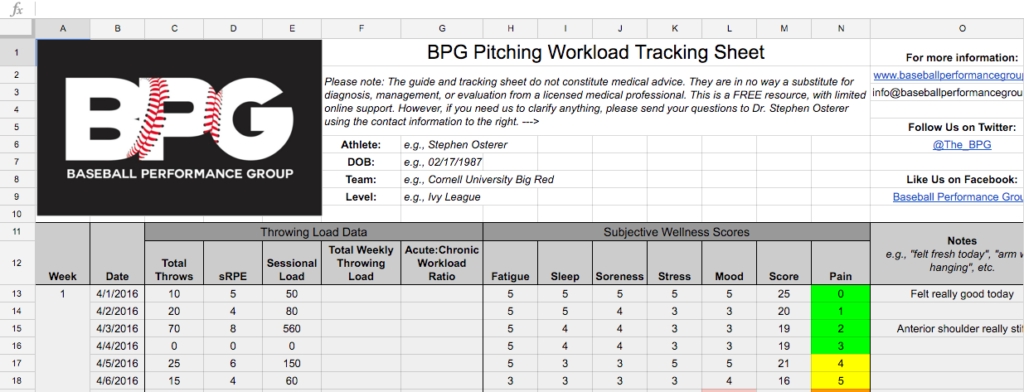

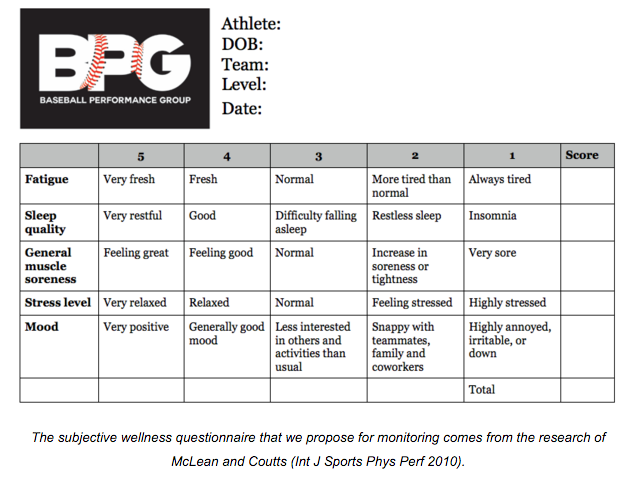

The core philosophy behind his program was intelligent progression and graded exposure. We used a flexible approach to programming, collecting subjective and objective measures to steer us through different checkpoints along the way.

When we re-introduced throwing, we closely monitored his daily, weekly, and monthly throwing workloads, in conjunction with sessional RPEs, and subjective ratings of arm fatigue and soreness, so as to better manage his training program. We shied away from pain, but gradually introduced feelings of discomfort and fatigue, while continually observing how his body and nervous system reacted to new training stimuli.

As the season drew closer, we found out that he was slotted to be the closer for his team, and we tailored our preparation strategy accordingly. We adjusted his daily and weekly throwing load, limiting him to 20-30 maximum intensity throws per session, twice per week (making tweaks depending on our monitoring data) to simulate the demands of a college closer.

Heading into the pre-season period, he was pain-free and in high spirits. Things were going really well and we were confident that he was in the best shape of his life. This year was going to be different for him.

In his first pre-season bullpen he hit 91 MPH, matching a career high. Needless to say, we were both PUMPED.

A few weeks later, he locked down 3 saves in his first 3 appearances of the season, and was throwing 89-91 for strikes.

The two of us sent texts back and forth, excited at how well he was doing and celebrating the fact that he was finally pitching competitively again and free of pain. I started thinking to myself, “Now that he’s healthy, I can’t wait to see how many MPHs we can gain next off-season. Hell, maybe we can even take a run at the draft.”

Unfortunately, this isn’t one of those feel-good Cinderella stories.

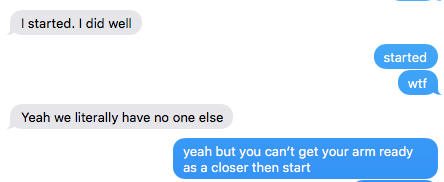

On April 2nd, I received the following text message:

From what I was told, his coach had decided that his starting pitching wasn’t working out, and he needed this pitcher to throw more innings. He had started a few games in the previous season, so it must have seemed like a reasonable idea. And so, a few days before the weekend, he was asked to help out his team by starting a game.

He threw well, going 6 innings, giving up just 3 hits, 1 ER, and locking down the “W”.

Success, right?

Sitting miles away, in a different country, I was fuming. I kept asking myself, “Does an NCAA coach really not understand that preparing to be a closer only prepares you… to be a closer? That spending your entire off-season getting your body and mind ready to throw 15-25 pitches and call it a day, does not prepare you to throw 80+ on any given day?”

Asking a closer to make the transition to starting pitcher in the middle of a season is about the most surefire way to get him injured. And you’re talking about a kid who has already had Tommy John surgery!

I was worried. I almost wished that he got lit up in his start. Maybe that would’ve convinced the coach to keep him in the bullpen.

After being told by the pitcher that his coach wouldn’t put him back in the bullpen because he needed him to win baseball games, all I could do was plead with him to be safe. To be as careful as he could. To shut it down if there was any hint of pain.

His second start was dreadful. He didn’t get past the 3rd inning, hung out to dry for over 90 pitches.

At this point I was more than worried…

I was scared.

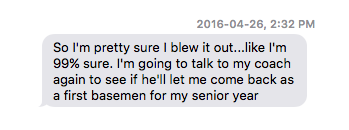

One week later, my deepest fears were realized:

My heart sank.

This kid spent the last 8 months busting his ass. He did everything right. And, he was finally making progress after years of frustration and disappointment. He was falling in love with the game again. And, in just three short weeks, it all came undone; his season was over.

I immediately blamed the coaching staff. Were they really unaware that this pitcher was unprepared to throw that many pitches AND was in pain trying to do so? Shouldn’t common sense tell them that he wouldn’t be able to handle a nearly 500% increase in workload? How can this even happen at the NCAA level? I really didn’t (and still don’t) understand.

But, maybe it’s not just the coaches fault. Maybe the athlete never communicated to the coaching staff that he was in pain. Maybe he even told the coach he felt great. But why did he throw in those games if he felt like something was wrong? Was he scared to admit that he wasn’t healthy? Was he worried about letting his teammates down?

All of the questions circled in my head, leaving me exasperated with the situation. It took me a couple days to cool down and collect my thoughts, which I posted last week on Facebook:

(1) Monitoring workloads (i.e. throwing load) is an integral part of a successful and healthy transition from the off-season to the pre-season to the competitive season. Establishing and monitoring a pitcher’s chronic workload provides a baseline of his “capacity” (in this case, his ability to handle throwing-related stress) and can help the coaching and/or training staff set appropriate acute workloads (i.e. the number of throws in games and/or practice) on a daily and weekly basis.

If the coaching staff in the second scenario was actively tracking how many “competitive” or “high effort” throws Pitcher B was accustomed to throwing on a daily/weekly/monthly basis, in addition to how he was subjectively responding to that throwing load (i.e. how he feels before, after, and days after throwing), then they woulda/coulda/shoulda identified the problem at hand almost immediately.

(2) Players need to feel safe in communicating how they are subjectively feeling. Pitcher A was able to openly communicate with his coach that he wasn’t ready on Opening Day, and was able to play an active role in guiding his own workloads based on how he felt on any given day. Pitcher B, on the other hand, didn’t feel safe advocating for himself.

(3) Common sense. Common sense. Common $%#@ing sense! Without ANY explicit knowledge of stress, fatigue, or acute:chronic workload ratios, it should make pretty damn good intuitive sense that a player who normally throws 1 IP/appearance for 5 weeks isn’t physically prepared to go out and give you 5-6 IP. The best preparation and the fanciest monitoring system in the world can’t protect against poor judgement.

(4) Young athletes deserve better. There’s no one I feel worse for than an athlete who has a history of injuries, begins to fall “out of love” with the game because of it, works his ASS off to finally be pain-free, starts enjoying the game again as a result, and then succumbs to injury because of ignorance, abuse, or a lack of common sense. It’s an awful, awful thing to happen to a kid… a kid.

One thing is abundantly clear to me: Something needs to change.

Over the last month, I, along with the rest of the BPG crew, have put a lot of time into creating a working document to help coaches, training staffs, athletes, or parents of athletes, monitor throwing workloads. We think/hope this document will help coaches everywhere get a better indication of whether they are asking too much of their pitchers, how their guys are responding to their current workloads, and, finally, help identify any red flags, if and when they come up. I strongly believe that it will help prevent avoidable injuries like the one my client suffered.

Our workload guide is currently being tested by a few coaches, and we hope to unveil Version 1.0 in the very near future.

In the meantime, I strongly urge you as a coach to use common sense and create an environment where athletes feel comfortable discussing how they feel both physically and mentally. And, if you’re an athlete, do yourself the justice and please: Advocate for yourself. Injuries like Pitcher B are preventable.

Sincerely,

Steve