Questioning Conventional Practice for Pitchers

Pitchers at Practice

“If pitchers spent as much time practicing and performing joint mobility work as they do on PFP’s per week we’d see a significant difference in performance & injury reduction”

This came up in a conversation with a few guys in ta training session last week, with all of them nodding their heads in agreement.

“Not even that, if we just spent half the time we do shagging fly balls on moving better, that would work too,” another trainee chipped in.

It seems like such an obvious suggestion. A conversation that you’d think wouldn’t be necessary in 2018 with the infinite amount of freely available information.

But that’s still not reality.

I know that there are coaches and programs out there that spend their time critiquing and questioning their current practices, trying to poke holes in what they do. There are those who go out of their way to ask the question ‘why?’ without hesitation and are eager to adapt and evolve.

If you’re one of those coaches, have you ever considered exactly what you’re asking of your pitchers at practice?

What does a pitcher need to accomplish on any given day?

The answers to this question are plentiful, wide ranging, and of course, dependent on the time of year. It’s hard to definitively state anything, but some of the general boxes that we would want to check off may include:

- Skill acquisition

- Team unity

- Recovery

- Movement

- Conditioning

The conversation I had with my players got me thinking, so I wanted to address some of these points.

Conditioning

Should pitching coaches, hitting coaches, or baseball coaches in general be prescribing conditioning work?

In an ideal world, the answer is of course not. The overwhelming majority of baseball specific coaches do not have the training necessary to develop an appropriate plan for conditioning – that’s just not in their realm of expertise.

With that said, things are never ideal and simply doing our best is a reality that we must face. Most NCAA programs don’t currently have an S&C coach guiding conditioning work; be it on the field or pre-planning it with coaches. Instead, most programs require their baseball coaches come up with a game plan, typically on the fly, for what players are going to complete for conditioning daily.

This is a case where it’s potentially worth investing the resources to have an S&C coach come up with a logical conditioning plan. One that fits into the rest of the players training schedule.

Regardless of who sorts out the conditioning, I don’t see why it needs to take up so much time during practice. A good aerobic base can be maintained with two days of work. We don’t need to condition pitchers for the sake of conditioning five days / week (although we could chase adaptations with certain players).

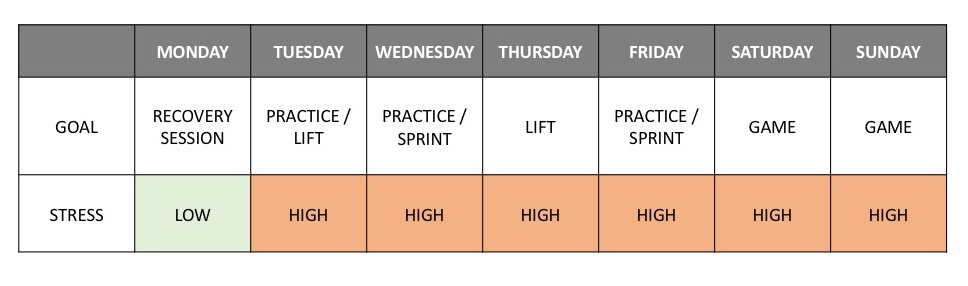

A schedule that is horizontally dense in stress could be a big problem for already stressed out collegiate players.

Moreover, from a stress density standpoint, why not include conditioning during lifts, and keep practice as a separate and distinct? Athletes, especially collegiate ones, probably need more times of low stress and placing hard conditioning on practice in the days in between lifts may be causing more harm than good. You’re essentially forcing them to put their foot on the gas five + days / week.

Shagging Fly Balls

Considering the following statements:

“Sitting is the new smoking”

“Standing is the new smoking”

“Not moving is the new smoking”

Why on Earth would we think that baseball pitchers, especially ones that fight gravity in an extended posture, would be well served to stand around for an hour every day. An athlete’s movement is constantly being shaped by the environment & the demands placed on it, and we should be encouraging athletes to encounter, adapt and express variant ranges of motion.

Does this guy really need to stand around for hours at a time?

If pitchers fight gravity with extension – they generally do – then asking them to stand around for hours / week isn’t just a waste of time, but potentially counter-productive to establishing greater movement capacity. We want our pitchers to express control of as much range of motion as they can handle. Forcing them to stand around doesn’t help with this.

Shagging fly balls, in my opinion, doesn’t check off any of the boxes you’d want to see in a practice. If you’re concerned about shagging fly balls from a logistics standpoint, as in who is going to pick up the balls otherwise, I get it. You may not be able to get around it. But I think that we should at least be creative in trying to.

PFP’s

My thoughts on PFPs have been outlined before. In short, conventional pitcher fielding practice doesn’t reflect the environmental, perceptual, or time pressure demands seen in a game and likely aren’t as beneficial as people believe. Much like taking BP at 60 MPH won’t dramatically help you hit a 90 MPH fastball with RISP in the bottom of the 9th , neither will fielding a fungo ground ball without game pressure, speed, context, or unpredictability.

I find it odd that most coaches would agree that pitchers need to train to become better athletes but refuse to see how taking groundballs like a bunch of robots won’t transfer.

If we want pitchers to be better pitchers, they need to be good throwers first.

If we want pitchers to be better at fielding their position, they need to be good fielders first.

Is Stroman able to make these plays because he’s an athlete or because he’s practiced non-contextual PFP’s? Photo cred: @pitchingninja

That means that pitchers should be taking groundballs from a variety of positions, speeds, and angles. PFP’s, if we’re going to spend time on them, should kinda be about making a pitcher a better middle infielder. (If you want to see the compete level and intensity go through the roof, try subbing that in for your standard PFP).

This doesn’t mean that (collegiate) pitchers shouldn’t ever practice standard base coverage, bunt plays, and come backers. It just shouldn’t take up very much time of the weekly schedule.

When a pitcher makes a play on roughly 1-2% of total pitches thrown, maybe we should be spending less time preparing for it.

Subbing in a ‘Movement Practice’

I’ll have to turn this into a longer post but I think that in years to come the way in which we go about practicing in college baseball will change.

Personally, I don’t think that we spend even remotely close to enough time focusing on movement. Movement is a broad term here, so let me refine what I mean.

We don’t spend nearly enough time on improving joint control plus strength (mobility) and movement pattern work.

What we’ve summed up so far is that we collectively spend a lot of time conditioning, doing PFPs, shagging fly balls, throwing during practice (and lifting throughout the week).

How much time do your pitchers spend taking care of their joints?

It doesn’t take a large logical leap to make the case that improving the things that make up the pitching motion will improve the pitching motion itself.

Joint ‘maintenance’ – taking an inventory of range of motion & intervening on deficits – should make up a significant portion of their daily routine. We know that range of motion changes endanger movement patterns and correlate to injury, but do we honestly take time to properly address it?

Do we empower our athletes to do so? Or are we shifting the accountability for joint health on passive care?

It’s strange to think that programs can spend hours / week dedicated to shagging fly balls and practicing 50 MPH ground balls & covering bases and maybe, maybe, spend thirty minutes on joint health.

I think that is going to change.

It appears that as a baseball community that we are trending in the right direction regarding improving the skill acquisition process. At last year’s Pitch-a-Palooza, it seemed like ‘Bernstein’ or ‘degrees of freedom’ was dropped in every presentation. This winter the Florida Baseball Ranch will be hosting a Skill Acquisition Conference for baseball (which I’m fortunate enough to present at) that push the game forward. Go on Twitter and you’ll see that Paul Nyman’s prediction of the next decade being “Constraints-Led” is already coming to fruition.

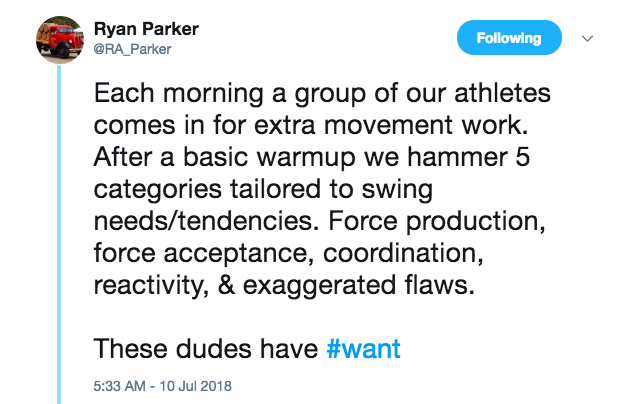

Look at what Ryan Parker and the guys at 108 Performance are doing.

My guess is that this attention towards refining how we go about improving movement (and therefore skill) will leak into practices more and more. Pitching coaches will have a better handle on influencing movement, being able to guide players through movement constraints, and potentially integrate everything into a comprehensive process that goes far beyond just throwing drills (more here).

The integration of therapy, training, and skill work is where we are heading. Whether that’s a coach that can assess joint health and teach mobility, a strength coach that understands pitching mechanics, or a therapist that can do either of the other two.

A New Model for Pitcher Practice

If I oversaw a collegiate (or even high school) program, pitchers wouldn’t practice PFP’s very often, conditioning would ideally be administered by an S&C coach and included during lifts, shagging fly balls would be reduced (or deleted), and I’d include much more attention to movement each practice – likely integrating that into skill acquisition work. The latter is something that I will address in a full article soon. Above all else, I’d use an overarching exercise classification system, like Bondarchuks CE, SDE, SPE, and GPE, to help organize the whole training program.

Parkinson’s Law states that “work expands to fill the time available for its completion” and I believe that in many cases we’re guilty of that with pitchers.

Everyone knows that the student-athlete lifestyle can be a difficult one. Whether that’s in high school or college, we know that athletes are generally overworked, overstressed, and not sleeping well (obvious outliers on both sides here). It is with that in mind that I think coaches should really question whether they are maximizing the pitchers’ time in practice. We are all ultimately ‘stress managers’ and we need to remain cognizant of that.

So, I ask, are you just filling up the time allotted for practice, or are your pitchers working on getting better?

Another beauty article!!!

Glad we have one fan, Graeme!!

Thank you. Your article is primarily about college ball, but it is even more urgent in youth baseball. Between youth baseball driven solely by adults, year round/travel baseball, 4-5 hour meaningless high school practices, multi-game youth tournaments every weekend, the drive for ‘exposure’ and college scholarships, it’s amazing that any kid would be physically able to play college baseball, or even want want to play college ball.

Moreover, teams are often employing methods with pitchers at the youth level that they’ve sort of heard about, but have no idea on how they should be implemented, or whether they should be implemented at all. They’re layering on additional levels of stress without any thought as to why they’re doing it.

An example; the local high school has now picked up in an uniformed way that ‘weighted balls and long toss are good’. The first practice, without evaluation or a progressive program, in the middle of January, all pitchers were throwing heavy balls, long toss and bullpens. Of course kids got hurt, but they are ‘the weak ones’. This mindset is pervasive at all levels.

Hopefully you and others will keep fighting this good fight for the good of college ball, but I pray for the future of the game that it also filters down to youth ball as well.

Thank you for the comments Paul. I think that this is a good example of how social media can go the wrong way. Instead of using the near infinite free information to improve the quality of a program, we are seeing a % of the population trying to simply ‘keep up’ with the trends without becoming informed first. It’s trying to keep up with the Joneses and that is just human nature.

I’m just glad that there are credible authorities putting out good messages – Eric Cressey is a great example – and trying to do our best to play a (much) small(er) role in improving the game.

Coincidentally, my son is actually at Eric’s collegiate program in Hudson for the summer…

I started reading Eric’s stuff when my first boy started pitching, as well as Wolforth, Boddy, Randy Sullivan, Lantz Wheeler, Graham Lehmann, Dan Blewett, your stuff… What I realized was that pitching was incredibly risky, particularly for a young arm.

After reading Eric and others, we realized early on that we can play other sports, that time off from baseball is ok, that more time and money spent on development, less time spent in playing endless travel ball games is a good thing.

We aren’t the norm however. In the world of travel ball, it’s often times a binary choice; you’re either in our your out. Unfortunately many parents get caught up in the temptation of the travel ball grinding culture. It seems to make sense- just put in the ‘10,000 hours’ of playing endless games and meaningless practices, and your son will get a scholarship or go pro. It pervades youth baseball, and it makes for a not fun and unhealthy experience for a lot of kids.

I wish you, Eric, etc. all the best. You’re going up against the headwinds of an entrenched culture, but baseball needs this sea change. Thanks for fighting the good fight…

Your son is in good hands.

We’re trying our best and appreciate the comments. Thanks Paul!