Keeping Up With Baseball Research: 6/25/2018

In the past, I tried putting together a somewhat consistent research review on relevant baseball research… let’s just say it didn’t work. To fully break down (in depth) a research paper, it’s methods, findings, and practical application, took far longer than I had anticipated and limited my ability to put information out there. It was far too time consuming to maintain any consistency.

With that said, I am still dedicating hours each week to staying informed on the scientific literature as it relates to baseball and wanted to somehow disseminate findings, share what I’m reading, and do my (small) piece in pushing the baseball community forwards.

I’ve decided that one way that I can do that is by touching on some of the studies that I’ve recently read every two weeks; the ones that I find interesting or relevant to baseball and include brief conclusions that can be made. The goal isn’t to go into depth with these papers but to bring them to the attention of our followers and keep my thoughts organized.

This will be the first instalment of what I hope to be a helpful series for the baseball community.

Relevant Baseball Research: June 25th, 2018

Recovery of Upper Extremity Sensorimotor System Acuity in Baseball Athletes After a Throwing-Fatigue Protocol (open access) – Brady L Tripp, Eric M Yochem, and Timothy L Uhl

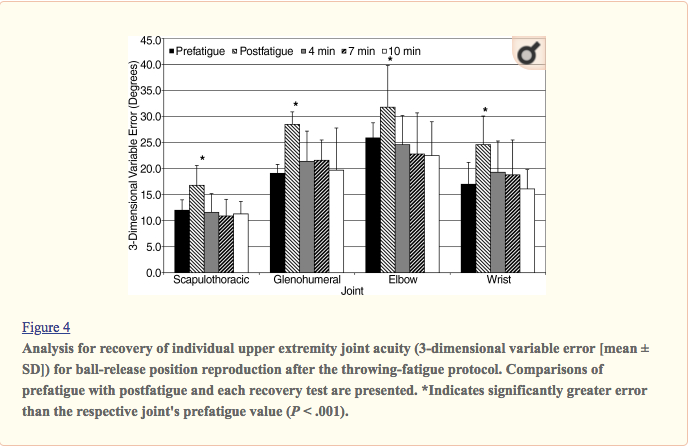

I posted about this study on Twitter last week, describing some of the methods, interesting findings and what it might mean for recovery. The authors looked into how fatigue, stemming from maximum velocity throws on their knees every five seconds, would affect position reproduction in the wrist, elbow, shoulder and scapula, in two different positions (arm-cocked and ball release). At 4, 7, and 10 minutes intervals post throwing, they found that almost all of the sensorimotor deficits from fatigue came back to normal.

That is, the negative affects of fatigue (as it relates to joint repositioning) were gone after 7 minutes – except for the glenohumeral joint in the arm-cocked position.

What this means: As it relates to recovery, and what I tried to get at in my recovery resource, it might serve us better to think of our post-throwing routine as more likely causing a training effect rather than recovering anything per se. In the case of joint repositioning, or restoration of the sensorimotor system, it seems that the deficits incurred from fatigue are likely gone within minutes, and it’s unlikely that rhythmic stabilizations or otherwise are going to return us to pre-fatigue levels any faster. This echoes what Proske spoke about in his landmark proprioception paper here.

*The glenohumeral joint didn’t return within 10 minutes in the arm-cocked position but the authors didn’t measure past that. More research needed.

Performance Metrics in Professional Baseball Pitchers before and after Surgical Treatment for Neurogenic Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (open access) – Robert W.Thompson, Corey Dawkins, Chandu Vemuri, Michael W.Mulholland, Tyler D. Hadzinsky, Gregory J.Pearl. Annals of Vascular Surgery Volume 39, February 2017, Pages 216-227.

There’s been a lot of talk about thoracic outlet syndrome in baseball over the last few years (some talk here, here, and here) with what seems to be an increasing number of cases and high profile victims. Mike Reinold even suggests that we might be not be catching a subclinical version of TOS, what he termed ‘transient neurogenic fatigue’, that could be responsible for decrements in command, velocity and overall performance. I like this theory.

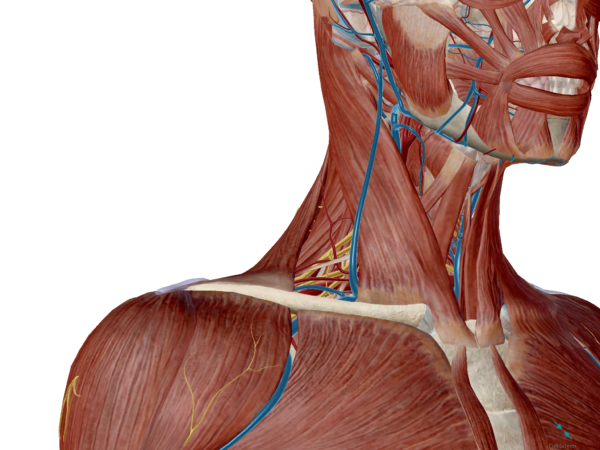

We know that it is most likely to be neurogenic in nature (95% ish cases are) and that neurovascular compression due to a host of potential factors are the likely culprit; hypertrophy in the muscles around the neck / shoulder girdle as an example. I’d even go so far as to suggest that incorrectly performing high volumes of bandwork isn’t helping the issue (read more here).

While perusing the literature last week, I came across an interesting epidemiological paper that tracked performance metrics in pro baseball pitchers before and after surgery for TOS. The study looked at the performance metrics of 10 of the 13 MLB pitchers who underwent surgical management for TOS between 2007 and 2014. There are some limitations to the study, including 3 of the 13 players undergoing TOS surgery not being included in the data set (also not knowing exactly why these 3 players didn’t make it back to the MLB).

Key findings:

“The results demonstrate that this cohort exhibited postoperative pitching performance capabilities largely equivalent to or better than those exhibited before surgical treatment. This provides the first such evidence that thoracic outlet decompression, along with an ample period of postoperative rehabilitation, can provide effective treatment for professional baseball pitchers with career-threatening NTOS.”

Do We Need a Cool-Down After Exercise? A Narrative Review of the Psychophysiological Effects and the Effects on Performance, Injuries, and the Long-Term Adaptive Response (open access) -Van Hooren, B. & Peake, J.M. Sports Med (2018) 48: 1575. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-018-0916-2

When I released my recovery resource a few months ago, I was a bit worried that I didn’t do a great job of summarizing the available research regarding active recovery, the ‘cool-down’ section. It is widely accepted that performing active ‘cool downs’ is a must post training or competition, but I found it difficult to back up or dismantle that claim with scientific evidence. The literature, at least what I was looking into, didn’t include many (if any) comprehensive reviews on the topic. It was a struggle.

Not anymore.

Thankfully, Bas Van Hooren and Jonathan M. Peake, two names you’ll find all over the sports science and recovery literature, dropped a literature review on active cool-downs. It’s the most comprehensive resource you’ll find to answer any question you’ve ever had on the topic.

You’ll be interested to read that their findings – or relieved that you didn’t mess up a recovery resource – generally do not stand up to the purported rationale behind their inclusions.

Once again, the answer to the question of whether or not we should include something in our athletes program comes down to ‘it depends’. Perceived benefit is powerful and speaks to the need for individualization. Along with many of the recovery strategies that we employ, choosing an active cool-down over passive rest, should be more about what an athlete believes is beneficial than the unlikely physiological effects.

Take home: read this entire article, and the co-authors (Peake, Van Hooren) other work. *Steve didn’t completely butcher the active recovery section.

Interesting stuff here. Thank you for compiling and sharing. Look forward to more

Thank you Sean! Will try and make this a bi-weekly thing.